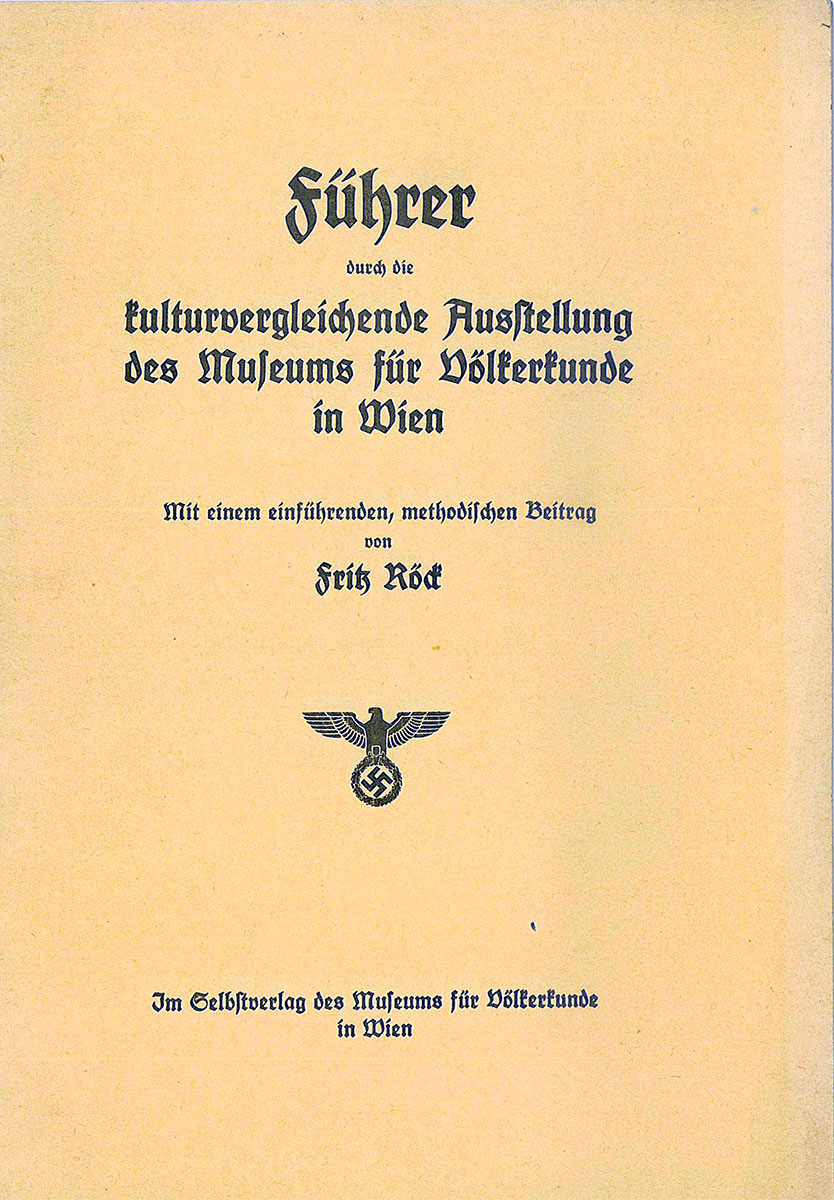

Inspired by Paris, London and Berlin, an anthropological society was also founded in Vienna in 1870; the decision was also taken to establish a museum of anthropology and prehistory complete with library. Much like the imperial ethnographic collections that preceded it, this museum also faced problems of storage space. The new building of the Imperial and Royal Court Museum of Natural History was the solution for the ethnological collections of the imperial house and this society. In this museum, opened in 1889, which emancipated itself from the Roman Catholic Church's interpretation of the world with its emphasis on Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, an anthropological-ethnographic department was established in whose development the Anthropological Society participated. The department covered not only ethnology and physical anthropology, but also European prehistory. The departments work was animated by misguided notions of evolutionary hierarchies reflected in ideas of “race”. These hierarchies saw so-called non-European “primitive peoples” and prehistoric European peoples as precursors of purported higher stages of human development. This definition of the world celebrated the idea of supremacy of Europe, colonialism, and the triumph of modern science. Some of these classification schemes, e.g., the notion of different human "races" and the distinction between folk art (simple and static), art and high culture (complex and dynamic), are still common today.

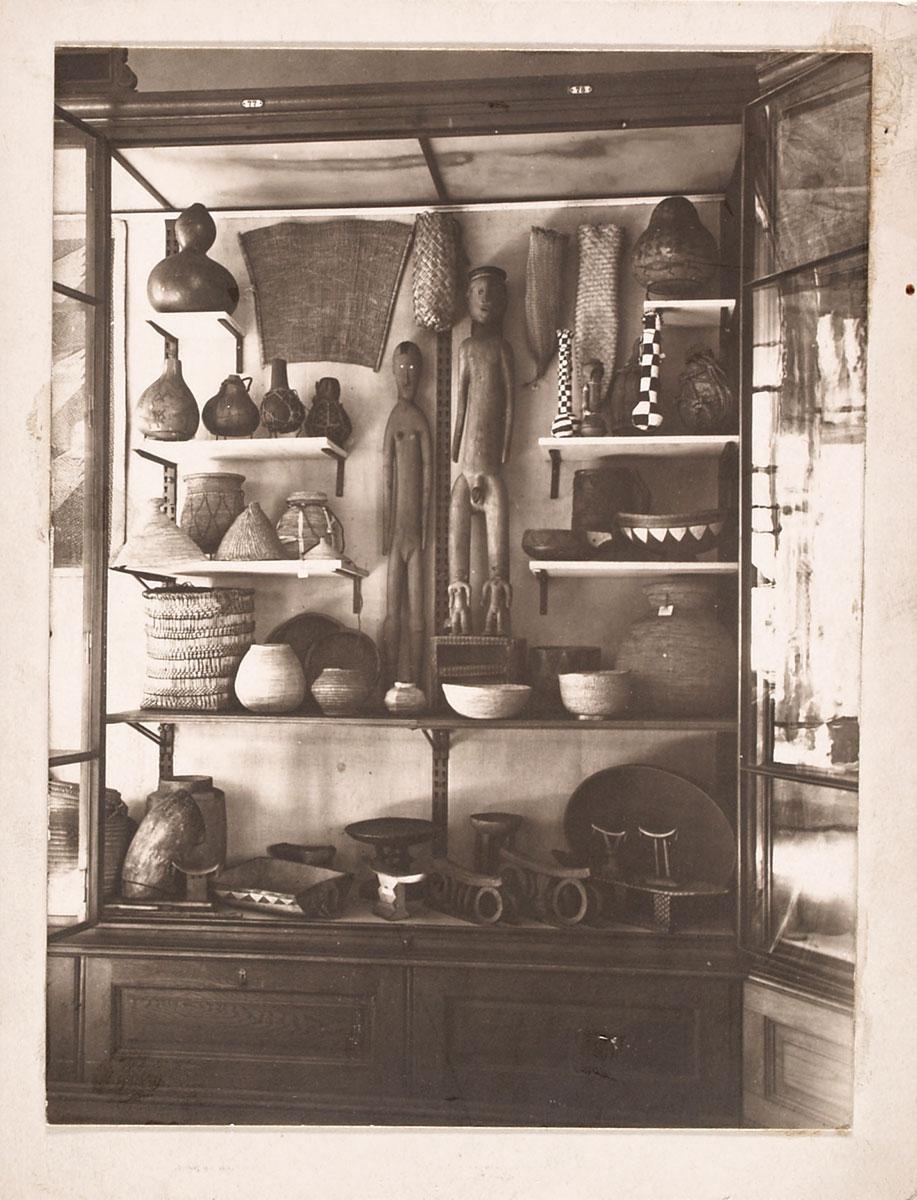

Due to competition from other museums and collectors, the department tried to expand the collections as quickly as possible in order to anticipate the disappearance of certain cultures expected at the time and to fill collection gaps; a practice that was also common in other countries at the time. In this way, the material heritage of mankind was to be safeguarded in order to enable a comprehensive study of its cultural history. But, as in earlier eras, “exotic” artefacts remained a focus of interest.

Adequate funding for acquisitions was a challenge. Thus, the department adopted different strategies: Individual patrons were courted, and the museum sought to exchange objects with other museums and with private collectors. Members of the diplomatic corps and colonial officials contributed significantly to the expansion of the museum’s collection. Although Austria-Hungary was not a colonial power in the mould of Britain, France and Germany, the museum was nevertheless a beneficiary of colonialism. The extensive collection from the Kingdom of Benin, which was subjugated by British forces and later bequeathed to the museum by a patron is a case in point.